By: Charles Bramesco | Monday, October 28, 2019 1:00PM EDT

The actor, director and activist talks about his return to the Stephen King universe and his frustrations with the state of the US

There’s an unmissable sense of the now in the second season of Castle Rock, Hulu’s anthology series recombining the best-known works of Stephen King. The Maine hamlet of Jerusalem’s Lot, first dreamed up by the master of the macabre as a feral vampire stronghold, contends with a more earthbound set of problems in its newest iteration. The opioid epidemic sweeping New England has seeped into town, driving area pharmacists to install locked glass cases for select products. More pressing still is the mounting tension in town between the Somalian immigrant community and the largely Caucasian local populace, each distrustful and fearful of the other. The impending turf war reflects a widening cultural divide in American life, as xenophobic sentiments gain traction with an increasingly vocal faction of reactionaries.

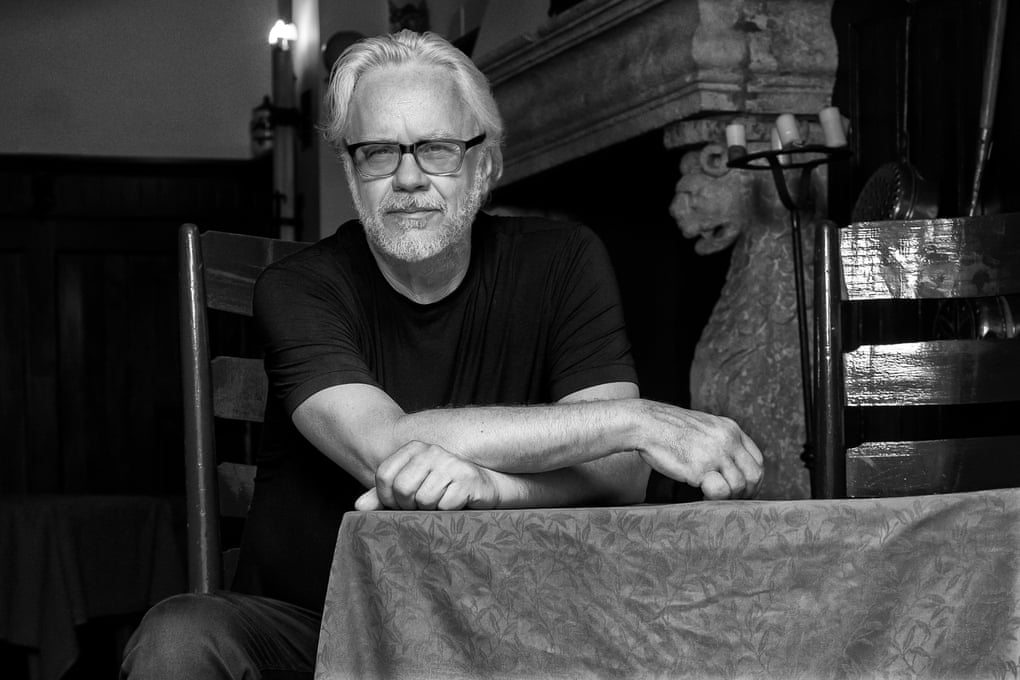

Tim Robbins, who portrays Reginald “Pop” Merrill, an ailing Jerusalem’s Lot crime boss, is glad to talk about returning to King’s dark world for the first time since the ubiquitous 1994 adaptation of The Shawshank Redemption. He politely praises the variety of the novelist’s writing, the smoothness with which stories set in our own reality drift into more “batshit crazy” dimensions. But the 60-year-old actor really gets animated when conversation turns to the more broadly political subtext of the show, about tribalism and the average suburb as a battleground in the culture wars.

“There’s a metaphorical element to this town, as a stand-in for small towns all over America,” Robbins tells the Guardian from a hotel suite overlooking Central Park South, and from there he’s off. He’s fine with talking showbiz – but he’s got bigger things on his mind.

Crime and punishment – their arbitrary definitions, the imperfect methods by which they’re put into practice – have taken up more of Robbins’ waking thought as of late. He sees jumping-off points for larger debates everywhere in his work. Musing on the show’s depiction of a widespread drug addiction, Robbins says: “We live in a society that has purposefully criminalized drug use as a punishment.” He recently directed a documentary to this effect, using the feature 45 Seconds of Laughter to chronicle his time spent teaching prison inmates commedia dell’arte as unconventional therapy.

“I’ve worked with guys serving life sentences for possession of marijuana based on the three-strikes law,” he recalls. “When I was doing Shawshank, I talked to the actual prison guards working as extras and asked them what they would change about criminal justice if they could change anything. Most of them said they’d legalize marijuana, which really surprised me at the time. The guards were saying it’d make their jobs so much easier, it’d make more space in facilities. Then they said that if you don’t have the courage to do that, at least organize inmates by violent and non-violent offenders. A lot of these prisoners are kids sentenced to one or two years, and because there’s a one-and-a-half-year waiting list for GED and job training programs, we’re putting these kids into what they called ‘crime school’. They saw what growing up incarcerated does to a child.”

Read more

The constant throughline of Robbins’ career has been the marriage of his activist bona fides with his chosen work. His directorial debut, Bob Roberts, took a bite out of early 90s conservative doctrine, imagining a charlatan who charms the GOP with faux-lksy wisdom. (When asked where Bob Roberts would be in 2019, Robbins shrugs. “Maybe he’d be in the White House.”) Robbins hopes that his next film, Todd Haynes’ legal drama Dark Waters, will “start a dialogue about corporate crime, and institutions versus individuals”. And he seems to be capable of steering any particular aspect of Castle Rock to something wider and more meaningful.

In King’s predilection for haunted native burial grounds, Robbins sees a painful awareness of national sin. “In the world of Stephen King, physical spaces are haunted by the ghosts of the past,” he says. “Did you see the James Baldwin documentary I Am Not Your Negro? One of my favorite movies of the past few years. One of the things that still resonates with me was Baldwin talking about how we’ll never be right as a society until we learn to truly accept responsibility. People need to understand their own history.”

He illustrates that notion with The New Colossus, an original play from Robbins and his theater company, the Actors’ Gang. With 12 actors from twelve different parts of the world speaking twelve different languages, they tell the story of “their ancestors’ journeys from oppression to freedom.” The performance comes with discourse built right in, as Robbins and the actors speak after the show with the audience about themes of immigration and national identity. They ask for a show of hands on a series of questions – who’s an immigrant, who has immigrant parents, grandparents – designed to expose how much we all have in common.

“Many came to America to pursue something; many came against their will,” Robbins says. “But with the exception of America’s native tribes, we are all new here. That’s the character of our country. People saying: ‘No, I will not accept the world I’m living in.’ It’s having that moral strength, then having the physical strength to actually leave and make a dangerous journey. And then, once you’re here, having the strength to build a life from scratch. This is America’s DNA. The servants at Jamestown who jumped over the wall and said that they didn’t want to starve while a bunch of aristocrats had so much, they were Americans.”

Theater has given Robbins a creative avenue that splits the difference between his passions for entertaining and taking direct action. He’s taken a stage production of Nineteen Eighty-Four to Hong Kong and Colombia, where Orwell’s subtext all but overtakes the story on the surface. He penned a play called Harlequino: On to Freedom and got censored in China – not for the rabble-rousing anti-establishment content leading Shanghai crowds to bursts of spontaneous applause, but for a handful of off-color phallic jokes.

Can someone so dialed-in to the ills of the world, someone unable to stop thinking about all that is wrong, still find cause for optimism? Robbins is a subscriber to the old maxim to think globally and act locally: “In order to not be living in frustration about things you can’t change, it’s important to find something that you can change. It might just be in your own life, but that’s the first step.” It helps to section off time to get away from “the keyboard reality”, as he calls it, where the buffer of a laptop screen allows for too much “hatred in the abstract”.

Mostly, though, he’s staying in his lane and plugging away at the work of bettering what he can better. “Our time has great potential for change,” he says, adding: “It’s just that the power resisting that change is pervasive.” The age-old struggle continues, in other words, and he’ll continue to stake out his own little corner of it. Whether dispelling specters for Stephen King or bringing commentary to the four corners of the globe, he’s staying on his beat without taking his eyes off the big picture.

Castle Rock is now streaming on Hulu